“VISIONS AND VISIONARIES” CATALOGUE

£30.00

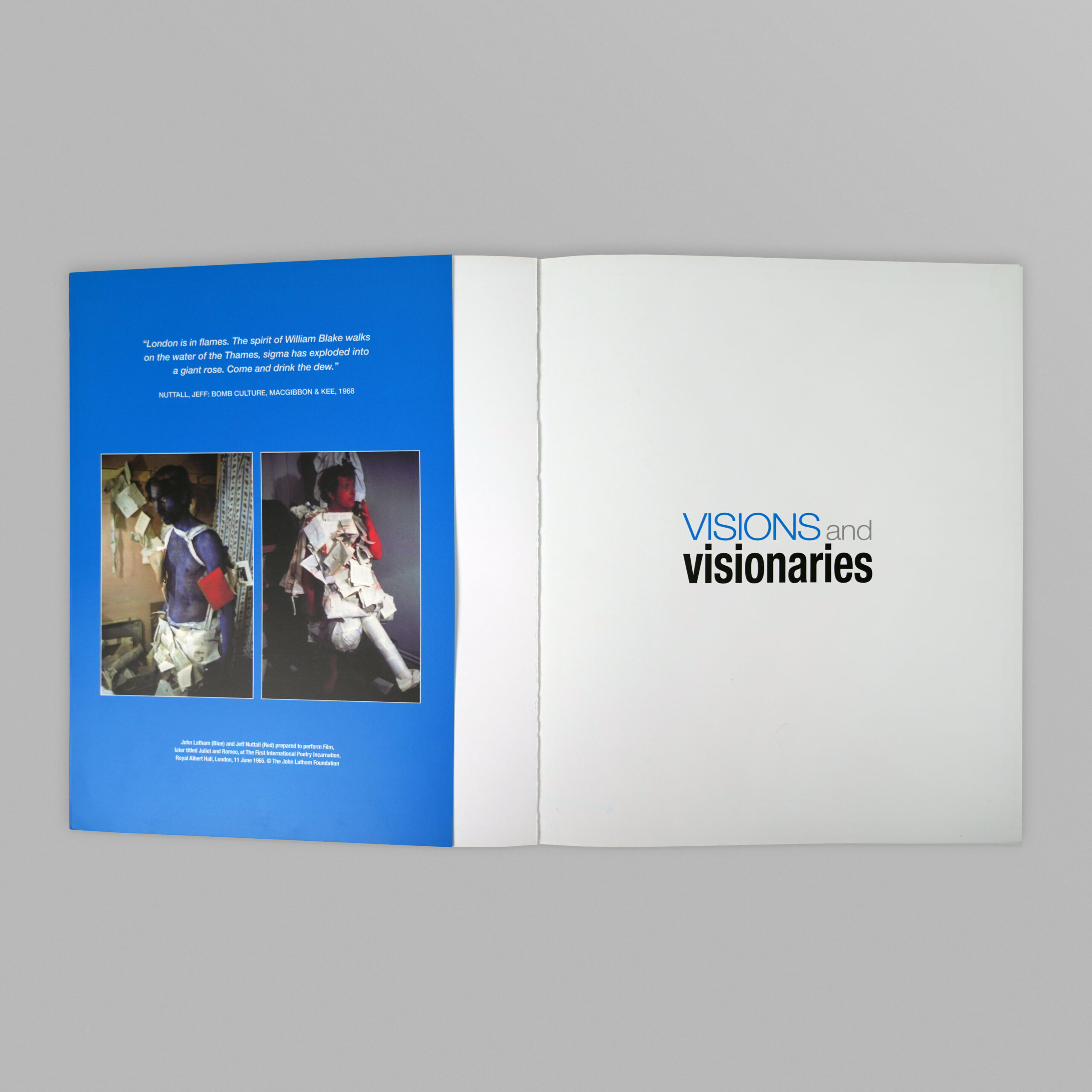

“VISIONS AND VISIONARIES”

Visions and Imaginings in Blake, Burne-Jones, Allen Ginsberg, John Latham and other masters.

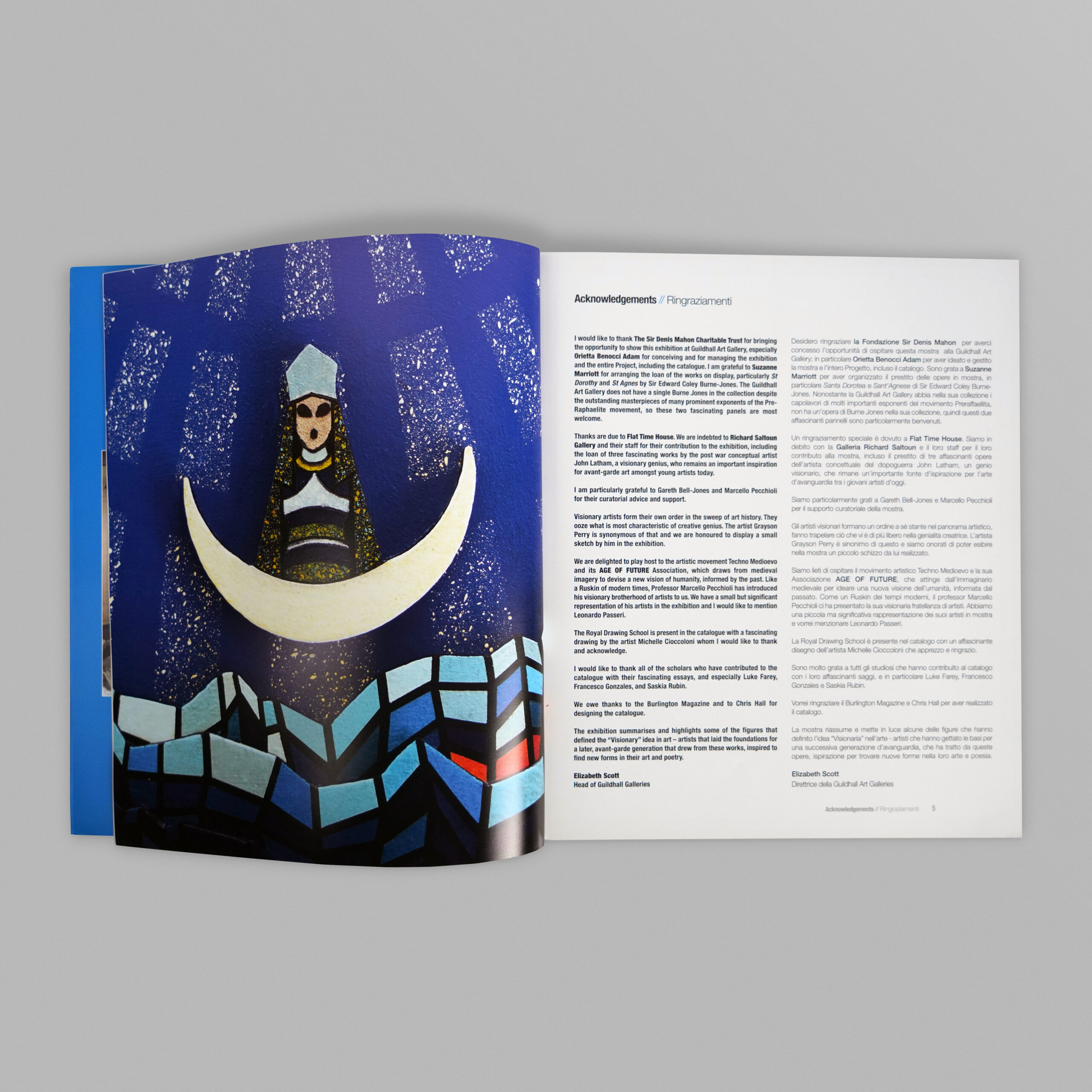

The Sir Denis Mahon Foundation

The Guildhall Art Gallery, London

11 December 2018 – 30 April 2019

Design and Production: The BURLINGTON Magazine

Printed by Gomer Press, Llandysul, Ceredigion

ISBN: 978-1-9164641-0-0

Languages: English

Visionary artists form their own order in the sweep of art history. They ooze what is most characteristic of creative genius.

In this exhibition we examine some artists who lived in the nineteenth century. They made the “visionary” into a poetic manifesto, the germ of an idea that is still relevant in the contemporary world with artists such as Geoffrey Fletcher, John Latham, Grayson Perry, or in art movements like Technomedioevo, proving that a visionary quality in art is not linked to any single period in history.

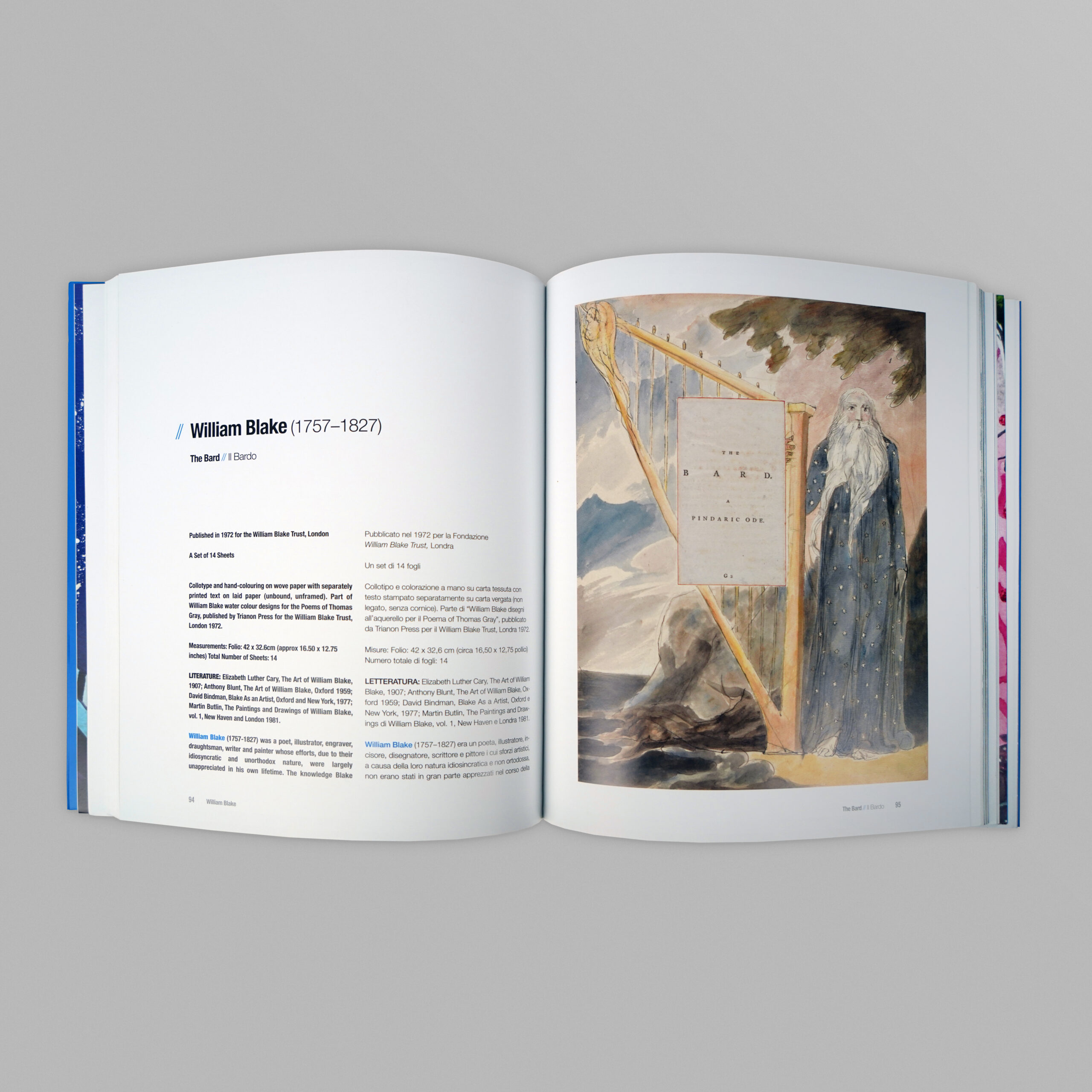

Our journey begins with the great figure, William Blake (1757-1827). Blake, a fierce enemy of rationalism and Enlightenment, conceived the imagination as a faculty capable of operating and creating things magically. In a series of prints inspired by the poems of Thomas Gray, “The Bard”, published in 1757, and in the series “The Fatal Sisters”, Blake gave free rein to his imagination and artistic vision, contributing to the renewal of mythology in British art. A generation after Blake lived Edward Coley Burne-Jones (1833-1898), one of the most important exponents of the Pre-Raphaelite movement. Burne-Jones made preparatory cartoons depicting St. Agnes and St. Dorothy, together with other figures for a stained glass window in All Saints’ Church, Cambridge. His work for the church is a testament to Burne-Jones’ symbolist vision, and a sign of the artist’s attempt to achieve divine resonance – a feat already realised by Blake’s famous work, Jacob’s Ladder (c.1800), and taken up again by Burne-Jones in The Golden Stairs (1880).

In John Constable’s work, Salisbury Cathedral from the Meadows by contrast, we find a visionary world with different emphases, in which the vision of nature is given symbolic meaning and endowed with rich autobiographical details. Different again is John Gilbert’s work, “The Enchanted Forest” (1886). A painting full of suggestions, this work describes several characteristics of “visionary” painting: the recovery of ancient literature, the use of evanescent colours, the “fairy tale” style of storytelling and the use of precious light effects. The same emphasis is apparent in Sir John Everett Millais’ watercolour, entitled “Lorenzo and Isabella”. This work is fundamental to Pre-Raphaelite culture, combining “history painting” with a new and original Pre-Raphaelite style in which fable and realism merge.

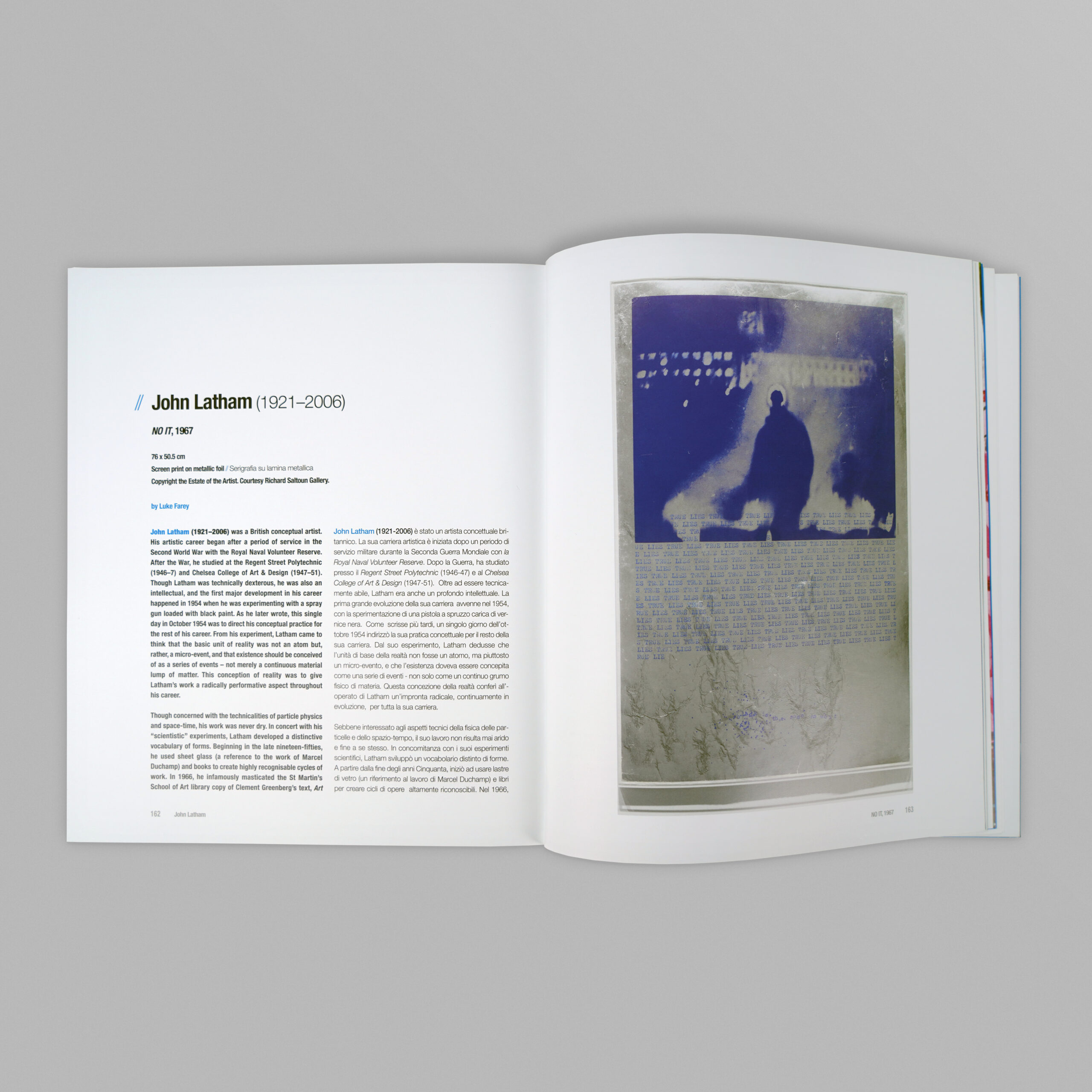

What influences in twentieth-century art can we trace to the visionary world? The connection between American writer Allen Ginsberg, British poet Jeff Nuttall and William Blake is typical. Blake’s influence on the Beat Generation is probably more significant than that of any other writer or artist. A fine thread also passes through John Latham’s work. Latham (1921-2006) was a visionary and an intellectual who looked to the cosmos with a desire to represent the sum and limits of man’s knowledge. His complex vision, in its restless experimentation, relates to the artistic movement TECHNOMEDIOEVO and its AGE OF FUTURE Association, which draws from medieval imagery to devise a new vision of humanity.

The exhibition summarises and highlights some of the figures that defined the “Visionary” idea in art – artists who laid the foundations for a later, avant-garde generation that drew from these works, inspired to find new forms in their art and poetry.

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.